Published online May 16, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i14.3224

Peer-review started: January 9, 2023

First decision: February 15, 2023

Revised: February 27, 2023

Accepted: April 6, 2023

Article in press: April 6, 2023

Published online: May 16, 2023

This is a secondary database study using the Brazilian public healthcare system database.

To describe intestinal complications (ICs) of patients in the Brazilian public healthcare system with Crohn’s disease (CD) who initiated and either only received conventional therapy (CVT) or also initiated anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy between 2011 and 2020.

This study included patients with CD [international classification of diseases – 10th revision (ICD-10): K50.0, K50.1, or K50.8] (age: ≥ 18 years) with at least one claim of CVT (sulfasalazine, azathioprine, mesalazine, or methotrexate). IC was defined as a CD-related hospitalization, pre-defined procedure codes (from rectum or intestinal surgery groups), and/or associated disease (pre-defined ICD-10 codes), and overall (one or more type of ICs).

In the 16809 patients with CD that met the inclusion criteria, the mean follow-up duration was 4.44 (2.37) years. In total, 14697 claims of ICs were found from 4633 patients. Over the 1- and 5-year of follow-up, 8.3% and 8.2% of the patients with CD, respectively, presented at least one IC, of which fistula (31%) and fistulotomy (48%) were the most commonly reported. The overall incidence rate (95%CI) of ICs was 6.8 (6.5–7.04) per 100 patient years for patients using only-CVT, and 9.2 (8.8–9.6) for patients with evidence of anti-TNF therapy.

The outcomes highlighted an important and constant rate of ICs over time in all the CD populations assessed, especially in patients exposed to anti-TNF therapy. This outcome revealed insights into the real-world treatment and complications relevant to patients with CD and highlights that this disease remains a concern that may require additional treatment strategies in the Brazilian public healthcare system.

Core Tip: This real-world study assessed intestinal complications (ICs) in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) undergoing therapy available in the Public Healthcare System in Brazil over the last 10 years. Outcomes suggests that patients that received conventional therapy and eventually anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy have an active and progressive illness, developing relevant ICs that might imply in considerable use of resources from the health system, CD remains a concern which may require additional strategies in the Brazilian public health care system.

- Citation: Sassaki LY, Martins AL, Galhardi-Gasparini R, Saad-Hossne R, Ritter AMV, Barreto TB, Marcolino T, Balula B, Yang-Santos C. Intestinal complications in patients with Crohn’s disease in the Brazilian public healthcare system between 2011 and 2020. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(14): 3224-3237

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i14/3224.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i14.3224

Inflammatory bowel diseases are chronic relapsing immune-mediated disorders of the intestine, and Crohn’s disease (CD) is one of its main representatives. CD is a global disease with rising incidence and prevalence across several countries[1]. In 2018, Martins et al[2] found a prevalence of 14.1 cases per 100000 inhabitants in Brazil[2]. The prevalence of CD in the State of São Paulo, Brazil, in December 2015 was 24.3 cases per 100000 inhabitants[3]. CD can affect the entire intestinal tract and is characterized by symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and mucosal ulcerations, among others. In addition, the disease presents complications such as malnutrition, stenosis, hemorrhage, perforation, obstruction, and fistula, which compromise the patient’s quality of life[1,4]. Disease flares and complications may result in the need for hospitalization and even surgery resulting in high direct healthcare costs[5].

Currently, there is no cure for CD, and the goal of medical treatment is to reduce the inflammation that triggers signs and symptoms and improve long-term prognosis by limiting complications. The choice of drug therapy for CD is influenced by several factors, including efficacy, need for induction and/or maintenance of remission, side-effect profiles, long-term risks, and patient choice. The treatments available include aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, and advanced therapies, such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors (anti-TNF), anti-integrins, and anti-interleukins. However, from 2011 to 2020, only the anti-TNF drugs infliximab, adalimumab, and certolizumab were available through the Brazilian public healthcare system. Several studies in humans have reported the positive impact of anti-TNF drugs on disease progression[6,7]. They are efficacious in inducing remission and reducing the need for surgery, hospitalization, and other complications[5]. Although effective, anti-TNF therapy are associated with a risk of serious and sometimes life-threatening treatment-related adverse events, such as potential for development of skin lesions, immune reactions, perioperative complications, infections, cancers, and decreased fertility/adverse effects on pregnancy[8].

Strategies have changed over the past decades to alter the progressive course of the disease[5]. The ultimate goal of medical therapy in CD, beyond achieving clinical response and sustained remission, would be to alter disease progression and prevent complications that lead to surgery[9]. An international study has reported that conventional therapy (CVT) might not decrease intestinal complications (ICs) or surgeries[9], whereas anti-TNF agents may present this ability. However, some population-based studies have documented the evolution of CD phenotype[9,10]. The present study aims to describe the ICs of patients with CD who initiated CVT between January 2011 and January 2020 in the Brazilian public healthcare system. An exploratory objective was to establish the ICs for patients who received infliximab, adalimumab, and/or certolizumab (anti-TNF subgroup) and patients who did not receive them (CVT-only subgroup).

This is a descriptive, non-interventional, retrospective claims database study using the Brazilian public healthcare system (DATASUS) to characterize ICs in patients with CD. Patients with at least one claim of CD international classification of diseases – 10th revision (ICD-10) code (K50.0, K50.1, or K50.8) and at least one claim of CVT (sulfasalazine, mesalazine, methotrexate, azathioprine, or associations) between 2011 and 2020 were included. The date of the first CD-specific claim for CVT was considered the index date.

All individuals aged ≥ 18 years at the index date (first claim of CVT) and who had at least one diagnosis record for CD [ICD-10 code of CD (K50.0, K50.1, or K50.8)] with a claim of CVT (sulfasalazine, mesalazine, methotrexate, azathioprine, or associations) were included. Patients who had anti-TNF therapy claims (infliximab, adalimumab, or certolizumab pegol) prior to CVT (index date), were non-Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS)-exclusive patients, had any ulcerative colitis ICD-10 codes (K51.0, K51.8, and K51.9) 12 mo prior to the index date, or had < 6 mo of follow-up in the database were excluded. Patients with any ulcerative colitis ICD-10 codes (K51.0, K51.8, and K51.9) 12 mo prior to the index date were excluded; for this reason, ICD-10 codes for ulcerative colitis were verified since January 2010. To capture the initial treatment stage, patients must have neither CVT claims 12 mo prior to the index date nor anti-TNF drug (infliximab, adalimumab, or certolizumab) claims prior to the index date.

Therefore, only the period from January 2010 to December 2010 was considered to assess the medical history, and the period from January 2011 to January 2020 was considered as the study period. After the index date, patients might have received anti-TNF therapy; therefore, a subgroup analysis was also considered: (1) Anti-TNF therapy cohort: Patients who presented at least one claim of anti-TNF therapy available at the public healthcare system (infliximab, adalimumab, or certolizumab), and patients who presented anti-TNF therapy either isolated or combined with CVT; and (2) CVT-only cohort: Patients who did not present any claim of anti-TNF drugs.

Four groups/categories of types of ICs in patients with CD were assessed: (1) CD hospitalization-related; (2) Procedure-related; (3) Associated diseases; and (4) Overall (one or more types of ICs). To be classified as an IC case, patients must present with at least one medical claim in one or more specific categories. Thus, IC was classified as CD hospitalization-related if the patient presented with a hospitalization claim due to CD (K50); procedure-related due to CD complications if the patient presented with a claim of procedure for rectum or intestinal surgeries described in SIGTAP (System of Table of procedures, medications and orthoses, prostheses, and special materials); and associated disease if the patient presented with any claim of the 33 ICD-10 codes predefined as common complications of the disease according to the literature and four independent clinical expert opinions. The ICD-10 codes include malignant neoplasm of the colon; stenosis; hemorrhage; ulcer; and diseases of the anus and rectum, megacolon, volvulus, intussusception, and erythema nodosum. The complete ICD-10 code list is described in Supplementary Figure 1, and overall CD complications if patient present one or more types of ICs previously mentioned (associated disease, procedures or hospitalization).

The primary endpoint was to assess the IC rate in patients with CD who received CVT, regardless of whether anti-TNF therapy was administered after CVT. As secondary endpoints, the IC rates were assessed in patients with no evidence of anti-TNF therapy (CVT-only cohort) and those with evidence of anti-TNF therapy (anti-TNF therapy cohort). The annual rate and incidence of ICs were assessed during the observational study period for patients with CD. Since each individual attended at different time intervals in the database, the incidence of ICs was converted to per patient/per year units, dividing them for all patients by the person-years of follow-up. Incidence rate (IR) was calculated as the number of intestinal events in the database divided by the total person-time at risk. Rates were stratified based on the definition of ICs: All types of ICs combined was denominated as overall and ICs segregated by types were expressed by associated disease, procedurerelated, and CD hospitalization-related, per 100 patient years (PY).

Additionally, secondary outcomes were used to describe patients who switched from CVT to anti-TNF drugs irrespective of whether the patient had prior ICs or switched from CVT to anti-TNF therapy after ICs. The treatment switch was identified as at least one claim of different drug (s) than the previous one independently of the gap (length of time without therapy) between drugs.

A further secondary outcome included ranking the 10 most frequent IC procedure-related and associated diseases (ICD-10 codes) according to the number of patients with at least one claim. Finally, demographic (age, sex, and location) profile of patients with CD included in the study was extracted from the database and expressed according to the cohorts: General patients with CD and subgroups, CVT-only, and anti-TNF therapy cohorts.

An exploratory outcome was to establish ICs (general and categorized by each type of IC) for patients who received infliximab, adalimumab, and/or certolizumab (anti-TNF subgroup) and those who did not receive them (CVT-only subgroup). For both groups, the total number of patients and claims for ICs, as well as the annual rate of ICs, were assessed.

DATASUS is the Informatics Department of the SUS (https://datasus.saude.gov.br/). SUS is available to the whole population and is the only source of healthcare for 75% of the Brazilian population[11], responsible for collecting, processing, and disseminating healthcare data in Brazil, of which most information is from the public healthcare system (SUS). All information in the database is constantly updated.

DATASUS databases are administrative claim data that include data on inpatient information systems (SIH[11]) and outpatient information systems (SIA[12]), which are used for payments and auditing in the public setting. SIH includes the causes of hospitalization according to the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). Data are presented as procedure codes from billing records and include demographic information, all procedures (whether the patient is hospitalized), number of procedures, and other additional information. All outpatient or inpatient procedures available in SUS follow the standardized procedure list SIGTAP. The ID code in SIA is able to link outpatient procedures to a single patient[13]; however, SIH does not have this ID coding. Thus, to allow for a longitudinal assessment in both systems at the patient level, a probabilistic record linkage was performed using multiple steps with different combinations of patient data from both the databases[14,15]. Ethical approval was not necessary as this was a secondary study that used anonymized data.

There is a supplemental system that coexists with the public system in Brazil, where nearly of 22%–25% of the Brazilian population is covered by private health insurance[16]. Some patients with private health insurance seek SUS to access high-cost medications while not seeking additional care within SUS, and no overall control is in place for dispensing most medications. To mitigate misleading results, patients that only used SUS to receive high-cost medications, but conduct treatment and healthcare partially by their private health insurance, were excluded. They were identified as patients who only had claims related to medication delivery (procedure code 06) without any claims related to other procedures (laboratory tests, exams, other therapies, hospitalizations, etc.).

As an observational secondary database descriptive study, no statistical hypothesis was intended, and only descriptive analysis was performed to describe ICs in patients who reported CD ICD-10 codes and underwent CVT in a public setting in Brazil.

The outcomes were summarized as absolute frequencies and percentages (%) for categorical variables and measures of central tendency and dispersion for continuous variables. Additionally, percentages were calculated over the number of patients with available (non-missing) data and Kaplan–Meier curves for time-to-event data. According to the type of variable the 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs), as applicable: Normal distribution for continuous variable, normal approximation to binominal distribution for proportion, and Poisson distribution for IR, as applicable.

The difference between the date of birth was used to calculate the age of patients and the first CVT and the time of follow-up according to the difference between the index date (CVT first claim) and the last date of patients available in the database. Timing of using CVT or anti-TNF therapy was calculated according to the date of the first and last claims of each drug reported by each patient, regardless of the gaps between them. The time taken for each drug was expressed as a continuous variable, such as mean, SD, median, and quartiles of the mean.

The CVT profile was expressed as the percentage of patients with at least one claim for sulfasalazine, mesalazine, azathioprine, or methotrexate. The anti-TNF therapy profile was expressed as the percentage of patients with at least one claim of infliximab, adalimumab, or certolizumab after the index date. The patients may have used a combination of therapies during the study period; however, this segregation was not performed. Switching CVT to anti-TNF therapy was defined as patients that had one or more claim (s) of a different drug than the previous claim.

The primary outcome was the IC profile of patients with CD after the initiation of CVT. ICs were assessed and expressed according to the total number of patients and total number of claims of each type of ICs per year after CVT initiation (annual ICs from 1 to 5 years). The mean (SD) and percentage of ICs per year were also calculated.

The total number of IC events (total number of claims), number of patients with at least one IC (first event), and total number of PY (defined as the time between the first claim of CVT therapy [index date] up to the last information available in the database for each patient) were expressed and used to calculate the IR (95%CI).

For the time-to-event analysis (Kaplan–Meier curve), it will be considered as censored the date of the last claim of the patient in the database or the date of the end of the study period for those patients without claim of ICs. The depiction of time to ICs in general population with CD and its subgroups (CVT-only and anti-TNF therapy) was described for all types of ICs (overall, procedure-related, associated diseases, and hospitalization-related). The time to switch from CVT to antiTNF therapy and time from the first evidence of anti-TNF to the first IC in the antiTNF therapy subgroup were also assessed.

ICs were not assessed according to CVT received or based on whether the patient discontinued or continued CVT. No imputation methods were used. Data were analyzed using Python version 3.6.9.

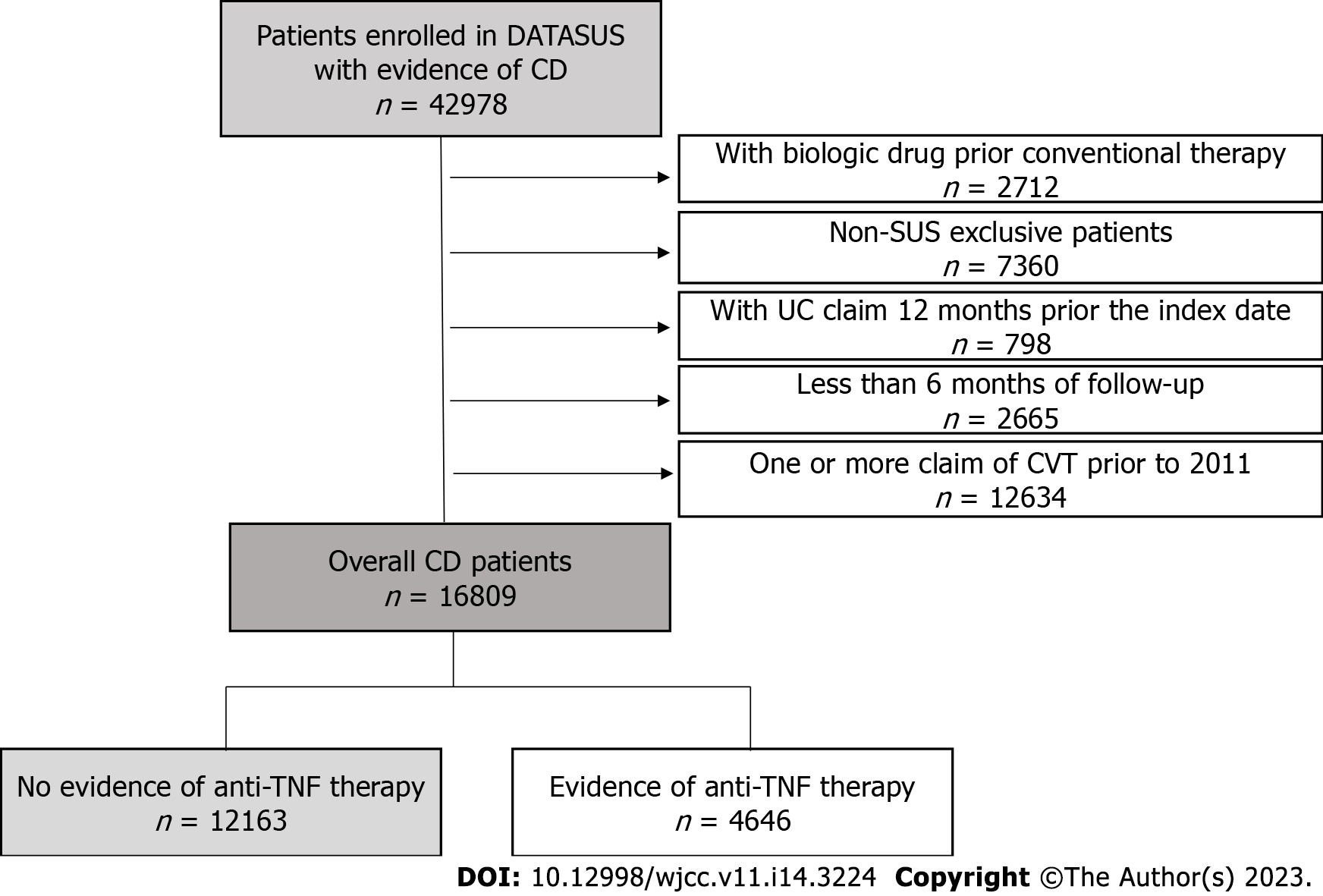

A patient attrition flowchart is presented in Figure 1. A total of 16809 patients with CD who received CVT met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 12163 (72.2%) had no evidence of anti-TNF (CVT-only) and 4646 (27.8%) had evidence of anti-TNF therapy after the index date. The patient’s demographic parameters are presented in Table 1 for all groups: Overall population with CD, CVT-only population, and anti-TNF therapy population. Over half of the patients resided in the southeast region and a minority in the North region of Brazil in all cohorts. Across cohorts, most of the patients were female (60%, 61%, and 54%) and Caucasian (53%, 51%, and 57%) for the general, CVT-only, and anti-TNF therapy populations, respectively. The mean age of 44 (± 15), 46 (± 15), and 40 (± 14) years and median (interquartile range) follow-up period of 4.34 (2.42–6.34), 4.17 (2.25–6.17), and 4.84 (2.92–6.84) years were found in the overall, CVT-only, and anti-TNF therapy populations, respectively.

| General patients with CD | CVT-only | Anti-TNF therapy | |

| Patients | 16809 (100) | 12163 (72) | 4646 (28) |

| Age, yr | |||

| Mean (SD) | 44.09 (15.38)4 | 46.37 (15.42) | 39.98 (13.72)5 |

| Median (IQR) | 43.27 (31.31–55.33)4 | 46.06 (34.10-57.62) | 37.53 (28.59-50.47)5 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 6804 (40) | 4686 (39) | 2118 (46) |

| Female | 10005 (60) | 7477 (61) | 2528 (54) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 8877 (53) | 6214 (51) | 2663 (57) |

| Mixed | 5002 (29) | 3108 (26) | 1330 (29) |

| Black | 622 (4) | 451 (4) | 171 (4) |

| Missing/others | 2308 (14) | 2390 (19) | 482 (10) |

| Region of residence | |||

| Southeast | 10241 (61) | 7085 (58) | 3156 (68) |

| South | 2369 (14) | 1765 (15) | 604 (13) |

| Midwest | 756 (4) | 491 (4) | 265 (6) |

| Northeast | 3188 (19) | 2668 (22) | 520 (11) |

| North | 254 (2) | 153 (1.3) | 101 (2) |

| Missing | 1 (0) | 1 (0.01) | 0 (0) |

| Follow-up time1, yr | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.44 (2.37) | 4.3 (2.36) | 4.86 (2.35) |

| Median (IQR) | 4.34 (2.42–6.34) | 4.17 (2.25–6.17) | 4.84 (2.92–6.84) |

| CVT | |||

| Mesalazine | 12423 (74) | 9376 (77) | 3145 (68) |

| Sulfasalazine | 2458 (15) | 1864 (15) | 619 (13) |

| Azathioprine | 7078 (42) | 4012 (33) | 3126 (67) |

| Methotrexate | 318 (2) | 180 (1.5) | 140 (3) |

| Anti-TNF therapy | |||

| Infliximab | 2737 (16) | - | 2737 (59) |

| Adalimumab | 2378 (14) | - | 2378 (51) |

| Certolizumab | 145 (0.8) | - | 145 (3) |

| Time using CVT2, years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.22 (2.46) | 3.16 (2.46) | 1.84 (1.75) |

| Median (IQR) | 2.67 (1.08–5.00) | 2.59 (1.00–4.92) | 1.25 (0.50–2.61) |

| Time using anti-TNF therapy3, yr | |||

| Mean (SD) | - | - | 2.39 (2.06) |

| Median (IQR) | - | - | 1.76 (0.67–3.67) |

| Time using CVT therapy prior to anti-TNF therapy | |||

| Mean (SD) | - | 1.84 (1.75) | - |

| Median (IQR) | - | 1.25 (0.50–2.61) | - |

| Immunosuppressant therapy prior to anti-TNF therapy, n (%) | - | - | 2603 (56) |

According to the inclusion criteria, all patients with CD had received CVT, and the mean time (SD) using CVT was 3.22 years (2.46; Table 1). Most patients used mesalazine (74%), followed by azathioprine (42%), sulfasalazine (15%), and methotrexate (2%). The percentage of patients who used each CVT drug was comparable across cohorts.

The mean time (SD) using CVT was 3.16 (2.46) years in patients with CD not exposed to anti-TNF therapy (CVT-only) and 1.84 years (1.75) in those who used CVT prior to anti-TNF therapy in the anti-TNF therapy cohort; in the anti-TNF therapy cohort, the mean time of anti-TNF therapy was 2.39 (2.06) years.

Among the 4646 patients who had evidence of anti-TNF therapy, 59% used infliximab, 51% used adalimumab, and 3% used certolizumab pegol, at some point in the study. Of these, 2603 (56%) patients presented with at least one claim of immunosuppressor drugs before anti-TNF therapy initiation.

Table 2 shows the IR of ICs in all cohorts. In the general CD group, patients had an overall IR (95%CI) of 7.48 (7.27–7.68) per 100 patients. The IR stratified by associated disease (ICD-10–related), procedure-related, and CD hospitalization-related ICs was 6.59 (6.39–6.78), 4.00 (3.98–4.15), and 0.61 (0.55–0.67) per 100 PY, respectively. In total, 14697 claims of ICs were reported from 4633 patients, of which 9429 claims were reported for IC associated diseases, 4707 for procedure-related ICs, and 561 as CD hospitalization-related ICs reported from 4162, 2706, and 454 patients, respectively.

| Total number of events | First event1 (n) | PY | IR per 100 PY (95%CI) | |

| General patients with CD (n = 16809) | ||||

| Overall (combined) | 14697 | 4633 | 61931.84 | 7.48 (7.27–7.68) |

| Associated disease | 9429 | 4162 | 63123.61 | 6.59 (6.39–6.78) |

| Procedure-related | 4707 | 2706 | 67528.54 | 4.00 (3.85–4.15) |

| CD hospitalization-related | 561 | 454 | 73645.51 | 0.61 (0.55–0.67) |

| CVT-only (n = 12163) | ||||

| Overall | 6415 | 3026 | 44431.39 | 6.8105 (6.5763–7.0447) |

| Associated disease | 5890 | 2739 | 45060.27 | 6.0785 (5.8579–6.2991) |

| Procedure-related | 2934 | 1768 | 47820.30 | 3.6972 (3.5281–3.8663) |

| CD-related hospitalization | 286 | 247 | 51654.41 | 0.5782 (0.4187–0.5377) |

| Evidence of anti-TNF therapy (4646) | ||||

| Overall | 3928 | 1607 | 17500.45 | 9.1826 (8.7548–9.6105) |

| Associated disease | 3539 | 1423 | 18063.34 | 7.8778 (7.485–8.2707) |

| Procedure-related | 1773 | 938 | 19708.24 | 4.7594 (4.4622–5.0567) |

| CD hospitalization-related | 275 | 207 | 21991.1 | 0.9413 (0.8137–1.0689) |

The IR of ICs was also expressed in the CVT-only subgroup (Table 2). In total, 6415 claims (reports) of ICs from 3026 patients were identified. The overall IR (95%CI) of ICs was 6.8 (6.5–7.04) per 100 PY, and the IR of associated disease, procedurerelated, and hospitalization-related ICs was 6.1 (5.9–6.3), 3.7 (3.5–3.9), and 0.58 (0.42–0.54) per 100 PY, respectively. Table 2 also shows the ICs in patients with CD with evidence of anti-TNF therapy. In total, 3928 claims for ICs from 1607 patients were found. The overall IR of ICs (95%CI) was 9.2 (8.8–9.6) per 100 PY, and the IR of associated disease, procedure-related, and hospitalization-related ICs was 7.9 (7.5–8.3), 4.8 (4.5–5.1), and 0.9 (0.8–1.1) per 100 PY, respectively.

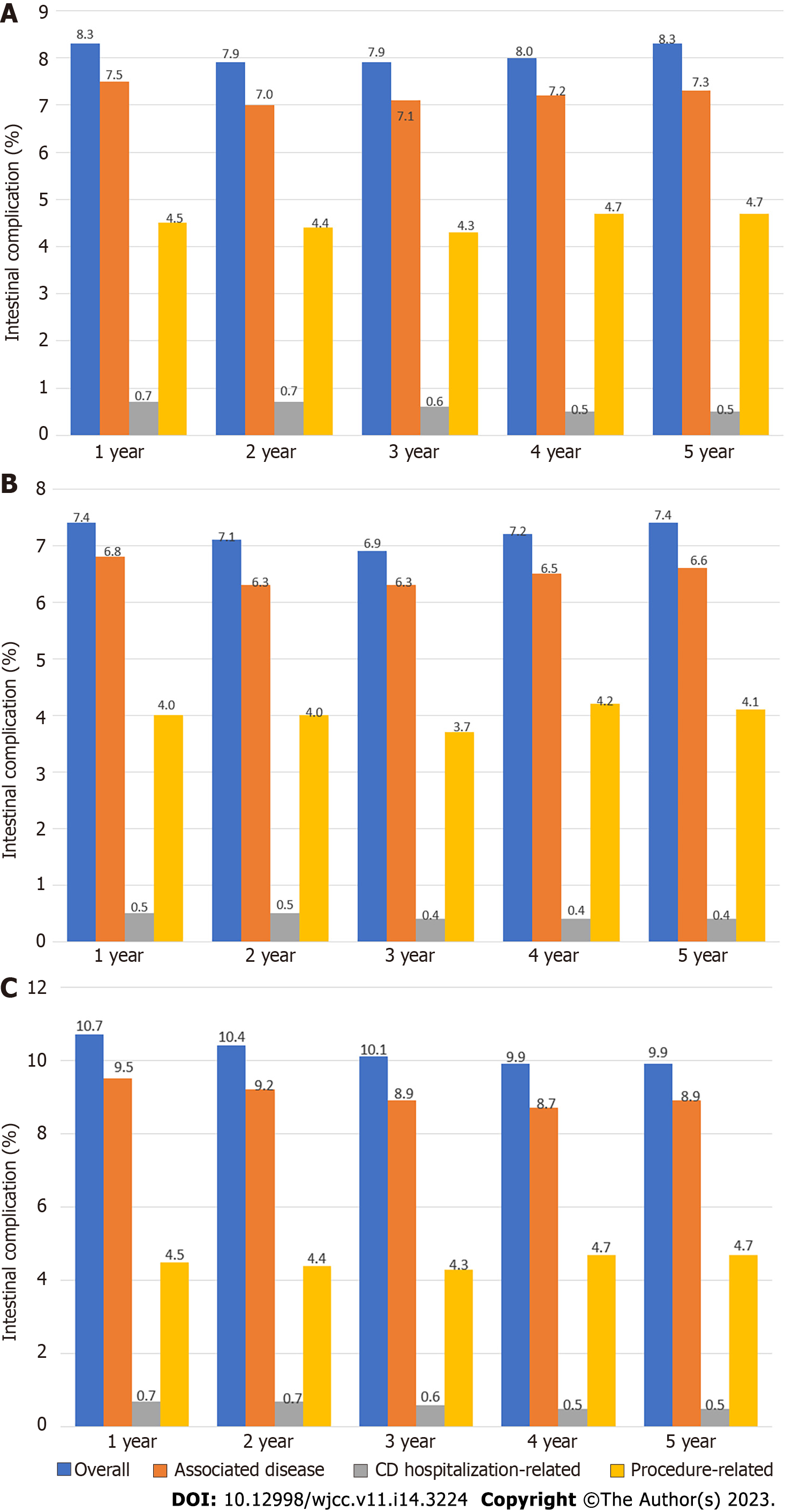

The annual rates of ICs (1–5-year period) in general, CVT-only, and anti-TNF therapy in patients with CD are described in Figure 2, respectively. In the first year after CVT initiation, 8.3% of patients in the general CD cohort, 7.4% in the CVT-only cohort, and 10.7% in the anti-TNF therapy cohort presented with at least one IC (overall), and in the fifth year, 8.3%, 7.4%, and 9.9% of patients presented with at least one IC (overall), respectively. The percentage and mean number of events per patient showed similar trends across the years.

The most common IC according to the type of associated disease (ICD-10–related) was anal fistula (31%) and that according to the type of procedure-related was fistulotomy (48%) in the general population with CD (Table 3).

| Associated disease (ICD-10–related complications) | Description | Number of patients with ICs associated diseases (n = 4162) | Percentage (%) |

| K603 | Anal fistula | 1270 | 31 |

| K610 | Anal abscess | 835 | 20 |

| R100 | Acute abdomen | 422 | 10 |

| K612 | Anorectal abscess | 406 | 10 |

| K635 | Polyp of colon | 401 | 10 |

| K629 | Disease of anus and rectum, unspecified | 350 | 8 |

| K632 | Fistula of intestine | 267 | 6 |

| K631 | Perforation of intestine (nontraumatic) | 251 | 6 |

| K602 | Anal fissure, unspecified | 229 | 6 |

| K601 | Chronic anal fissure | 174 | 4 |

| Procedure-related ICs | Number of patients with procedure-related ICs (n = 2706) | ||

| 407020276 | Fistulotomy | 1308 | 48 |

| 407020136 | Anorectal abscess drainage | 785 | 29 |

| 407020217 | Internal sphincterotomy | 350 | 13 |

| 407020179 | Enterectomy | 129 | 5 |

| 407020144 | Ischiorectal abscess drainage | 110 | 4 |

| 407020403 | Retossigmoidectomy | 105 | 4 |

| 407020209 | Enterotomy | 92 | 3 |

| 407020101 | Colostomy | 89 | 3 |

| 407020390 | Body removed – rectum or colon polyps | 83 | 3 |

| 407020225 | Excision of anorectal tumor | 78 | 3 |

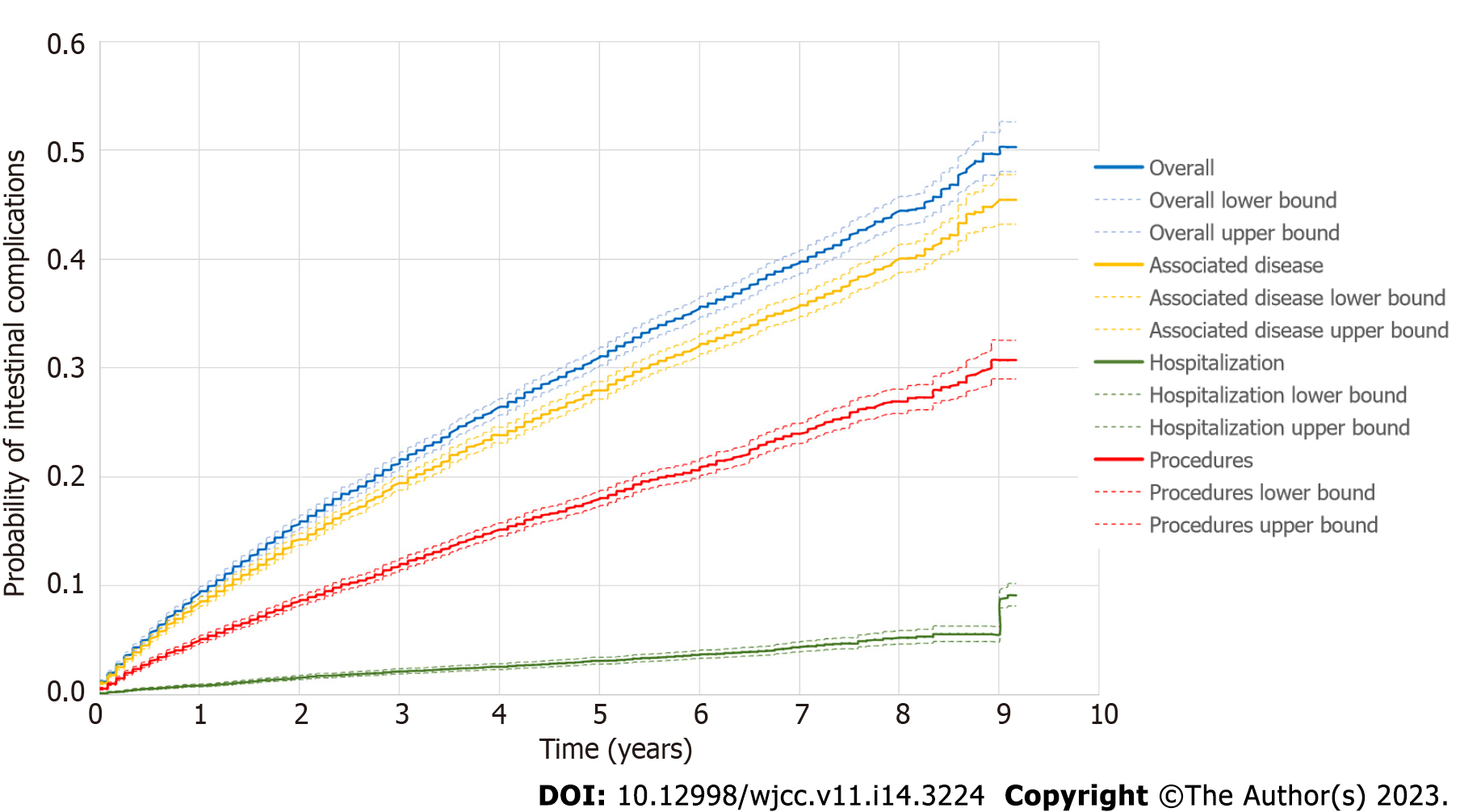

The visual representation of time-to-event (ICs) in the general cohort with CD according to the type of ICs is represented in the Kaplan–Meier curve (Figure 3), which suggests a decreasing trend of IC probability starting with the associated disease type, followed by procedure-related and CD hospitalization-related ICs.

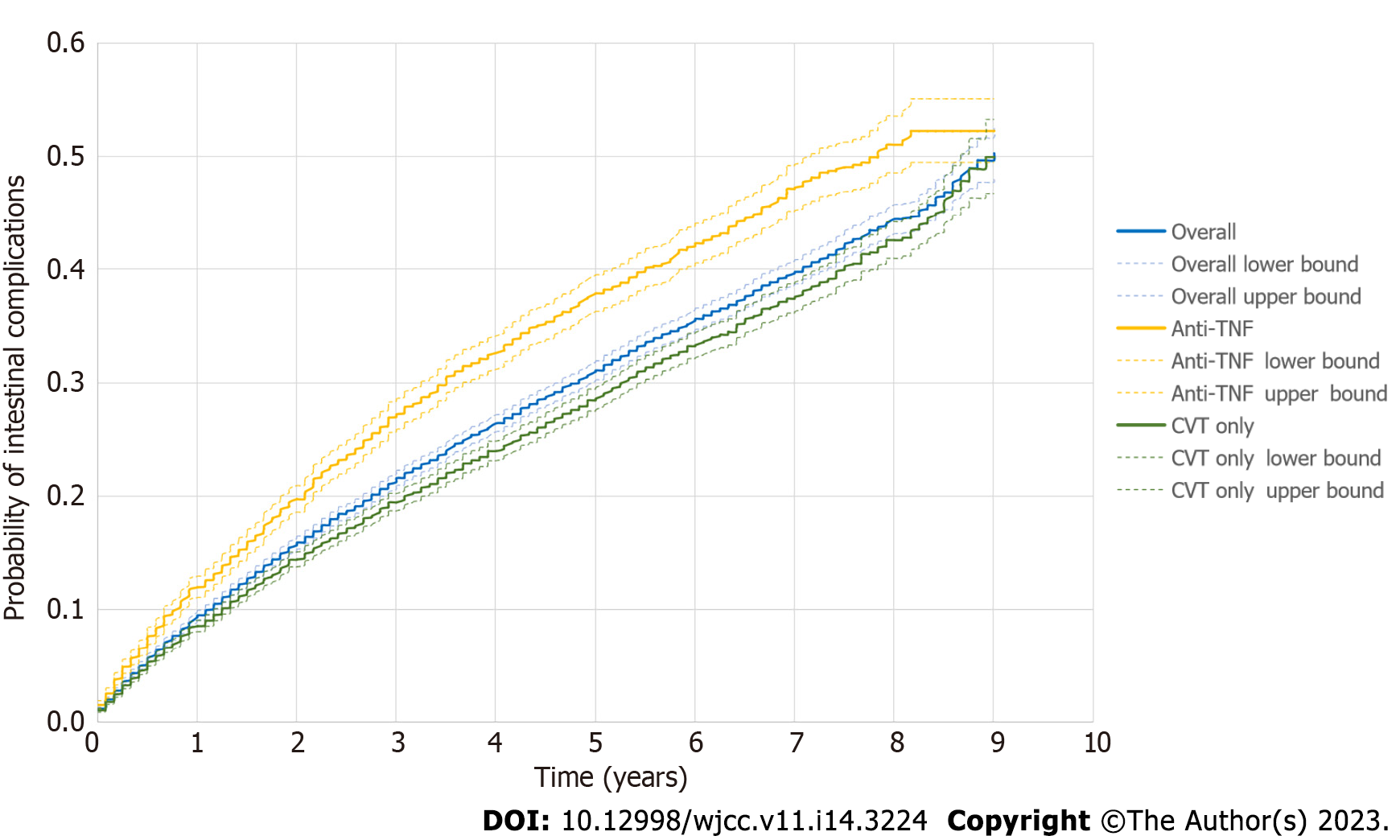

Figure 4 depicts the time to overall IC in the general population with CD, CVT-only, and anti-TNF therapy cohorts. The anti-TNF therapy cohort was the subgroup that sustained a shorter duration before an IC or censoring event.

Supplementary Figure 1 presents the Kaplan–Meier curve depicting the proportion of patients who switched from CVT to anti-TNF therapy, irrespective of whether the patient has had IC status. Among the patients in the anti-TNF therapy cohort, nearly 20%, 27%, 32%, and 38% were at risk of switching from CVT to anti-TNF therapy at 2, 4, 6, and 8 years, respectively, following their first CVT. Supplementary Figure 2 illustrates the time from CVT to anti-TNF therapy after the first IC claim (overall ICs). Approximately 15%, 22%, 30%, and 35% of the patients were at risk of switching from CVT to anti-TNF therapy at 2, 4, 6, and 8 years following their first CVT.

The current study revealed insights into the clinical and treatment characteristics enhancing evolution and progression of the disease relevant to patients diagnosed with CD and treated with available drugs in the public healthcare system in Brazil between 2011 and 2020. Although, methodological factors could contribute to underestimating numbers of ICs within the DATASUS database, it is possible to note an important and constant number of events over the years either in patients that have used only CVT or anti-TNF therapy.

A large proportion of patients with CD in our study were from the southeast and the minority in northeast regions of Brazil, which might be a consequence of discrepancy in reports and/or assistance across the regions of the country and lack and/or delay in diagnosing CD patients.

CD is a progressive illness, and absence of timely and effective treatment results in considerable cumulative structural damage and complications[17]. The goal of CD treatment is to achieve clinical and endoscopic remission, avoid disease progression, and minimize surgical interventions[8]. Some evidences indicate that CVT, including immunosuppressant agents, may be insufficient to control CD progression, resulting in complications and/or considerable surgeries rates[18]. Accordingly, applying pre-defined and validated types of ICs in our study allowed for the longitudinal assessment of disease evolution and progression across the years. Our findings show that the IR of ICs is nearly 7.5 per 100 PY in patients who received either CVT or anti-TNF therapy (general cohort). Approximately 8% of general patients with CD present with at least one IC in the first year of CVT. This proportion of patients with some ICs was sustained across the years up to the last year observed in the study (5 years).

Anal fistula (31%) was the most common ICD-related IC, and fistulotomy (48%) was the most common procedure-related IC. Corroborating our findings, Schwartz et al[19] (2002) reported that fistulas occur in up to 35% of patients with CD and perianal fistulas occur in 20%[19]. In general, fistulas rarely heal without treatment and require pharmacological treatment, and most surgery rates can reach nearly 83%[19]. Based on previous observations, invasive procedures, such as intestinal surgeries, are most commonly indicated for medically refractory CD, medication side effects, and complications of disease, including hemorrhage, perforation, obstruction, and fistula formation[20]. Considering the current structure of healthcare delivery in Brazil, surgery and other complex procedures are not uncommon, and even complementary exams are postponed due to the lack of resources and specialists in the system[21]. These could prevent the achievement of a real and necessary treatment approach to control CD in the public system, keeping patients longer in pharmacological therapy, even if a further invasive approach is necessary. The higher lifetime risk of chronic uncontrolled inflammation may exacerbate symptoms and complications[22] and may influence the treatment pattern and procedures described in the present database. CD is a progressive disease, and it is important to closely monitor patients with a high risk of progression by risk stratification, escalation of therapy, and availability of therapies with different mechanisms of action[4].

Observing the same variables in the CVT-only and anti-TNF cohorts, it is possible to note that patients who used anti-TNF therapy at some point in their treatment tended to present earlier and/or more cases of ICs than patients who did not use anti-TNF therapy, although no formal comparisons were performed.

A robust literature shows that adding anti-TNF drugs to the CD therapeutic scheme helps in decreasing the risk of surgery, hospitalization, and disease-related complications[23], in addition to improving the quality of life[22]. The higher rate of ICs in patients with CD exposed to anti-TNF therapy than in the other cohorts in the present study is somewhat understandable. Anti-TNF is prescribed more often for the treatment of moderate-to-severe CD and/or for those who have become refractory to standard treatment[24]. Furthermore, it is inherent that this subgroup includes patients with advanced and/or longer disease periods who are non-responders and/or failures to anti-TNF therapy. As a consequence of the method limitations, the natural course, time, and severity of the disease were not contemplate in the analyses due to methodological limitations. Therefore, the rates may have been affected by different clinical aspects besides the treatment approach.

In addition to anti-TNF, other drugs with different mechanisms of action might offer potent alternatives for controlling disease and preventing ICs in patients with CD. Reinforcing this, clinical trials showing the induction and maintenance of durable remission of novel molecules with mechanisms of action different from those of anti-TNF agents in patients with CD naïve and/or previously anti-TNF failure are growing and consistent[25,26]. However, studies comparing the safety and efficacy of anti-TNF agents and novel molecules are limited[20]. Some studies indicated no difference in terms of effectiveness[27], while some have suggested considerable benefits with novel molecules, such as vedolizumab[28].

The optimal timing of anti-TNF therapy represents another important concern in CD management[5]. Our study indicates that nearly 30% of the patients switched from CVT to anti-TNF treatment for a long duration using CVT before switching, even if they had any IC. Of those, only 15% of patients switched after having an IC, which might be due to the lack of availability of medications with other mechanisms of action in the public healthcare system. Better outcomes have been observed when biologic drugs are introduced early in newly diagnosed patients[22,29-31]. Access to care and early intervention, including biologic agents to treat inflammatory disorders, can be difficult to achieve in the Brazilian public healthcare system[32], and usually leads to more severe morbidity and failure of prolonged courses of treatment.

Our study has several limitations that need discussion. First, longitudinal and timedependent analyses of outcomes and drug exposures of interest are dependent on greater completion and accuracy; however, DATASUS may be limited in the data captured for these variables due to the nature of the data entered (reimbursement purpose). Second, CVT and anti-TNF treatment coverage is based on the first claim of each drug in the database and the reason for anti-TNF use could not be determined. Third, it is not possible to distinguish whether a patient might be receiving their drug at private institutions (out of pocket). Medications used as part of CD treatment also include other drugs, such as corticosteroid agents; however, not all of them are described in SIGTAP. Also, the availability of each conventional and/or anti-TNF drug at the SUS varies over time due to strategies, policies, national guidelines, and other factors. Fourth, although associated diseases, procedures, and hospitalization related to CD were carefully pre-defined as ICs, they did not cover 100% of all possible complications related to CD. Therefore, the complication rates could have been underestimated. In addition, event rates might be underestimated because data such as comorbidities requiring hospitalization might not be captured because the record linkage used to build a patient-level longitudinal cohort is ICD-10 dependent. To reduce this bias, we used broad procedural terms and ICD-10 related to possible complications.

This study assessed the progression and evolution of patients with CD representative of the real-world treatment approach available in the Brazilian public healthcare system from 2020 to 2021. We were able to find a consistent and important number of ICs in patients treated with CVT and eventually anti-TNF therapy, capturing associated disease trends, procedures, and surgeries’ patterns, as well as hospitalization rate due to the disease. Besides providing up-to-date IC estimates, our data indicate that CD remains a substantial public health problem in Brazil. Further strategies such as adequate access, earlier intervention, and/or inclusion of other drugs with different mechanisms of action might positively impact CD patients.

Patients with Crohn's disease (CD) undergoing therapy available in the public healthcare system (Sistema Único de Saúde) in Brazil over the last decade.

Observe patients with CD who initiated and either only received conventional therapy (CVT) or also initiated anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF).

Verify the real-world intestinal complications (ICs) of patients with CD in the Brazilian public healthcare system.

Patients with CD with at least one claim of CVT (sulfasalazine, azathioprine, mesalazine, or methotrexate). IC was defined as a CD-related hospitalization, pre-defined procedure codes (from rectum or intestinal surgery groups), and/or associated disease (pre-defined international classification of diseases – 10th revision codes), and overall (one or more type of ICs).

This study highlights a consistent rate of ICs over time in all the CD populations assessed, especially in patients exposed to anti-TNF therapy.

The Brazilian public health care system should continue to develop additional strategies for treading CD.

Effective CD treatment in Brazil’s public healthcare system may require additional strategies.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jin X, China; Zhou W, China S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Guo X

| 1. | Torres J, Bonovas S, Doherty G, Kucharzik T, Gisbert JP, Raine T, Adamina M, Armuzzi A, Bachmann O, Bager P, Biancone L, Bokemeyer B, Bossuyt P, Burisch J, Collins P, El-Hussuna A, Ellul P, Frei-Lanter C, Furfaro F, Gingert C, Gionchetti P, Gomollon F, González-Lorenzo M, Gordon H, Hlavaty T, Juillerat P, Katsanos K, Kopylov U, Krustins E, Lytras T, Maaser C, Magro F, Marshall JK, Myrelid P, Pellino G, Rosa I, Sabino J, Savarino E, Spinelli A, Stassen L, Uzzan M, Vavricka S, Verstockt B, Warusavitarne J, Zmora O, Fiorino G. ECCO Guidelines on Therapeutics in Crohn's Disease: Medical Treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:4-22. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 654] [Article Influence: 163.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Lima Martins A, Volpato RA, Zago-Gomes MDP. The prevalence and phenotype in Brazilian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:87. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gasparini RG, Sassaki LY, Saad-Hossne R. Inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology in São Paulo State, Brazil. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:423-429. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Feuerstein JD, Cheifetz AS. Crohn Disease: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1088-1103. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 184] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kwak MS, Cha JM, Ahn JH, Chae MK, Jeong S, Lee HH. Practical strategy for optimizing the timing of anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy in Crohn disease: A nationwide population-based study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e18925. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ha F, Khalil H. Crohn's disease: a clinical update. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2015;8:352-359. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Goulet O, Abi Nader E, Pigneur B, Lambe C. Short Bowel Syndrome as the Leading Cause of Intestinal Failure in Early Life: Some Insights into the Management. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2019;22:303-329. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Adegbola SO, Sahnan K, Warusavitarne J, Hart A, Tozer P. Anti-TNF Therapy in Crohn's Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 158] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Thia KT, Sandborn WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Loftus EV Jr. Risk factors associated with progression to intestinal complications of Crohn's disease in a population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1147-1155. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 481] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 502] [Article Influence: 35.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lovasz BD, Lakatos L, Horvath A, Szita I, Pandur T, Mandel M, Vegh Z, Golovics PA, Mester G, Balogh M, Molnar C, Komaromi E, Kiss LS, Lakatos PL. Evolution of disease phenotype in adult and pediatric onset Crohn's disease in a population-based cohort. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2217-2226. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bittencourt SA, Camacho LA, Leal Mdo C. [Hospital Information Systems and their application in public health]. Cad Saude Publica. 2006;22:19-30. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 113] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. |

Brasil, Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Regulação, Avaliação e Controle Coordenação-geral de Sistemas de Informação.

Manual Técnico Operacional SIA/SUS Sistema de Informações |

| 13. | Ali MS, Ichihara MY, Lopes LC, Barbosa GCG, Pita R, Carreiro RP, Dos Santos DB, Ramos D, Bispo N, Raynal F, Canuto V, de Araujo Almeida B, Fiaccone RL, Barreto ME, Smeeth L, Barreto ML. Administrative Data Linkage in Brazil: Potentials for Health Technology Assessment. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:984. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Justo N, Espinoza MA, Ratto B, Nicholson M, Rosselli D, Ovcinnikova O, García Martí S, Ferraz MB, Langsam M, Drummond MF. Real-World Evidence in Healthcare Decision Making: Global Trends and Case Studies From Latin America. Value Health. 2019;22:739-749. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Barbour J, Araújo A, Zanoteli E, França Jr MC, Ritter AMV, Casarin F, Julian GS, Yazawa P, Mata VE, Carlos NS. Healthcare resource utilization of spinal muscular atrophy in the Brazilian Unified Health System: a retrospective database study. J. Bras. Econ. da Saúde.. 2021;13:94-107. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Maia Diniz I, Guerra AA Junior, Lovato Pires de Lemos L, Souza KM, Godman B, Bennie M, Wettermark B, de Assis Acurcio F, Alvares J, Gurgel Andrade EI, Leal Cherchiglia M, de Araújo VE. The long-term costs for treating multiple sclerosis in a 16-year retrospective cohort study in Brazil. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0199446. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ferrante M, Karmiris K, Newnham E, Siffledeen J, Zelinkova Z, van Assche G, Lakatos PL, Panés J, Sturm A, Travis S, van der Woude CJ, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, Panaccione R. Physician perspectives on unresolved issues in the use of conventional therapy in Crohn's disease: results from an international survey and discussion programme. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:116-131. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cosnes J, Nion-Larmurier I, Beaugerie L, Afchain P, Tiret E, Gendre JP. Impact of the increasing use of immunosuppressants in Crohn's disease on the need for intestinal surgery. Gut. 2005;54:237-241. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 479] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schwartz DA, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, Panaccione R, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Sandborn WJ. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn's disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:875-880. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 739] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 634] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chang MI, Cohen BL, Greenstein AJ. A review of the impact of biologics on surgical complications in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1472-1477. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Viacava F, Oliveira RAD, Carvalho CC, Laguardia J, Bellido JG. SUS: supply, access to and use of health services over the last 30 years. Cien Saude Colet. 2018;23:1751-1762. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 85] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rubin DT, Griffith J, Zhang Q, Hepp Z, Keshishian A. The Impact of Intestinal Complications on Health Care Costs Among Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treated With Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Therapies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:1201-1209. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Singh S, Heien HC, Sangaralingham LR, Schilz SR, Kappelman MD, Shah ND, Loftus EV Jr. Comparative Effectiveness and Safety of Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Agents in Biologic-Naive Patients With Crohn's Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1120-1129.e6. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dalal SR, Cohen RD. What to Do When Biologic Agents Are Not Working in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2015;11:657-665. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Tarabar D, Hirsch A, Rubin DT. Vedolizumab in the treatment of Crohn's disease. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;10:283-290. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hahn L, Beggs A, Wahaib K, Kodali L, Kirkwood V. Vedolizumab: An integrin-receptor antagonist for treatment of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72:1271-1278. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Laredo V, Gargallo-Puyuelo CJ, Gomollón F. How to Choose the Biologic Therapy in a Bio-naïve Patient with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Clin Med. 2022;11. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sands BE, Lukas M, Fedorak RN, Lee S, Bressler B, Fox I, Rosario M, Sankoh S, Xu J, Stephens K, Milch C, Parikh A; GEMINI 2 Study Group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711-721. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1416] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1425] [Article Influence: 129.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ma C, Beilman CL, Huang VW, Fedorak DK, Kroeker KI, Dieleman LA, Halloran BP, Fedorak RN. Anti-TNF Therapy Within 2 Years of Crohn's Disease Diagnosis Improves Patient Outcomes: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:870-879. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pillai N, Lupatsch JE, Dusheiko M, Schwenkglenks M, Maillard M, Sutherland CS, Pittet VEH; Swiss IBD Cohort Study group. Evaluating the Cost-Effectiveness of Early Compared with Late or No Biologic Treatment to Manage Crohn's Disease using Real-World Data. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14:490-500. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Dulai PS, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Demuth D, Lasch K, Hahn KA, Lindner D, Patel H, Jairath V. Early Intervention With Vedolizumab on Longer Term Surgery Rates in Crohn's Disease: Post Hoc Analysis of the GEMINI Phase 3 and Long-term Safety Programs. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;15:195-202. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tundia N, Kotze PG, Rojas Serrano J, Mendes de Abreu M, Skup M, Macaulay D, Signorovitch J, Chaves L, Chao J, Bao Y. Economic impact of expanded use of biologic therapy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn's disease in Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, and Mexico. J Med Econ. 2016;19:1187-1199. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |